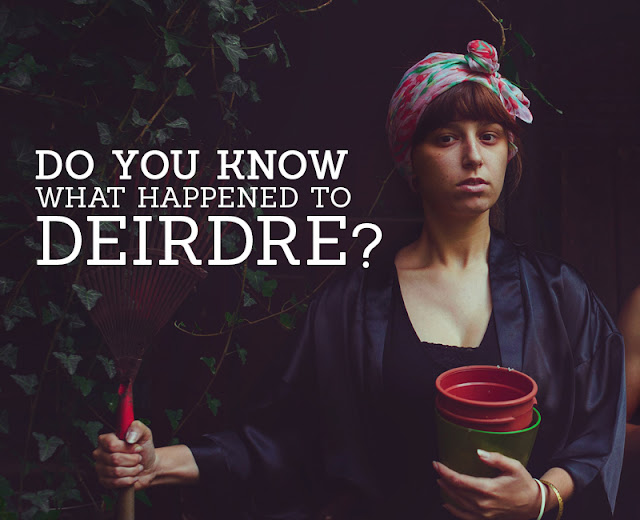

Deirdre of the Sorrows

It's one of the most famous tales in Irish mythology, but so many Irish people don't know anything about it. It's like a cross between Rapunzel and True Romance, Bonny and Clyde and the little mermaid, only it's hundreds of years older and much more bloody.

It's the story of a howl from the belly of a pregnant woman. She was preparing food for her visiting high king, Conchobor, when the unborn baby within her let out a craven screech, unlike anything anyone had ever heard. It was enough to set his soothsayer on his feet.

"This child is cursed," he said, "she will be born too beautiful for this world. She will cause horrors and bloodshed, war and mayhem." He took his seat again at the table. "It's what no one wants to hear, but you need to kill her now, before it's too late." The mother was horrified, letting out a screech of her own and dropping her serving dish onto the tiles, but the king stood by her. He promised to take the child away when she was born, raise her as his own in seclusion from the outside world where she could do harm and, when she was of an age, marry her and make her his queen. It was what no one wanted in particular, but it was the high king's will, he had spoken and so it was decided.

It was many years later that Deirdre was out in the enclosed yard, in the grounds of the high king's castle with her handmaid and the conversation had come around to talking about men, once again. In all her years, Deirdre had never seen a man. None had been allowed next or near her by the king, to provide against the horrible prophecy coming true. But still, she had in her mind the kind of man she would have preferred to the king. She pointed out a raven, drinking blood from the snow in a nearby field.

"When I'm of age, I'll have a man with skin as white as that snow, hair as black as that raven's feathers and cheeks as red as that blood, and I'll accept no other."

"You're promised to the king," the handmaid protested, "he's raised you to become a great queen."

"We shall see," Deirdre said.

It wasn't much longer until she found a man with exactly that appearance. He was working for the king in a nearby field. A young man by the name of Naoise, one of the sons of Uislu. Right away, she ran over to him and jumped on his back, refusing to let go until he agreed to run way with her and protect her from whatever happened. At first, Naoise refused, knowing full well Deirdre was promised to the king, but the more he looked at her, the more he realised he was already falling in love, and was ready to do anything for her. Finally, Naoise agreed to run away and take Deirdre with him. He recruited his brothers and formed a formidable party of warriors, fleeing into hiding from wherever the high king could find them. The king was furious, and dispatched a crew of ferocious trackers and killers to find them, headed up by Fergus, his most prized warrior, who hunted them to the very edges of the land and even as far as Scotland.

Finally, an offer was sent to Deirdre, Naoise and his brothers. The High King would spare their lives if only they would return to his castle with Fergus. Well, they deliberated. It seemed risky, but truly, they had no place left to go really, lest they stray into lands they had no knowledge of. Deirdre agreed and they gang were escorted back to the High King's castle. What awaited them there, however, was not forgiveness and certainly not amnesty. Naoise and his brothers were killed immediately by Fergus and his men, and dumped in a large pit, which was covered over quickly with fresh soil. Deirdre was left a prisoner again, only now it was to get even worse.

The tale ends with Deirdre aboard a chariot with Conchobor, the high king, and his chief warrior, Fergus.

"Deirdre," Conchobor asked, "whom do you hate most in all the world? Is it me?"

"No, sire, it isn't. Not quite."

"Who then?"

"Why, it's Fergus. The man who murdered my beloved and his brothers."

"Very well then. As a punishment for trying to escape, you shall be shared between myself and Fergus for the rest of your days. "

This final horror was too much for Deirdre. She looked ahead and spied a low hanging rock approaching and then, when it arrived, she raised her neck so it would catch her head and take it clean off. This was her final revenge against her king.

So there you have it. Not the cheeriest of tales, but then this is Ireland. If you were interested enough, I'm launching Sour. my novel based on the myth at a bookshop in Dublin on November 5th. More details here if you're interested.

Or read an Amazon Kindle sample here: