Saturday, 30 January 2016

Saturday, 9 January 2016

New Goodreads giveaway!

Enter for a chance to win one of five Author-signed copies of 'Sour', the latest, most unusual mythological thriller from Pillar Publishing.

A re-telling of ‘Deirdre of the Sorrows’, updated to the modern day, re-imagined with bizarre local characters and set in a fictional Irish countryside. In a desolate Irish town a local paper boy goes missing. Conall, a beetroot-faced, mule of a man, makes it his business to find the boy. What starts out a small undertaking, unfolds into a journey of strange rural experience, bizarre natural occurrences and warped small-town morality, revealing the shocking tale of a young girl horribly imprisoned and two boys fixed on rescuing her.

Posted by : Unknown

Saturday, 12 December 2015

Here are the first five pages of my book. If you like them, why not go ahead and buy it?

Conall Donoghue sours his porridge with at least two lemons. I know it because I can see into his kitchen from my kitchen, and I can see him pounding away with that spoon, eating his oul porridge under his light-bulb of a morning, or plunging his sink for teabags, or trying to make that dog bring him slippers without chewing through them for holes. You’d want to see him sitting there behind his paper each breakfast, and his wife Molly, driven twelve fifteenths demented with him ranting about the exchange rate on the yen. Make you sick so, he would.

Now, from here I can’t see what goes on in the other rooms. I can only see the kitchen, the back porch, the hall, the guest bedroom, a third of the back garden, through the side passage and into the driveway. And when the shed light is on, part of that too, but I’m sure I can pretty much bet the house he’s on about the same kind of crap in all of those places as well. He spends an ungodly portion of his time in that kitchen, though. Behind that paper, ranting and yammering about the Middle East and Kate Beckinsale’s overbite, eating his oul stews. My heart goes out to that poor unfortunate woman in there, with him since he retired. Man lost his mind soon after that, you ask me. Ask anyone. He was coming home, see, one night from Brady’s, late, with the dog Red Bob, when he witnessed a fatal accident. I think that changed him. It was steady stout and whiskey since a horse of his came in good the three o’clock at Chester, and that dog was like a guide dog to him on the unlit roads that run in this part of the world. He fumbled to hold tight on to its ears the full four mile limp home after closing up, and if he fell or wandered out onto the road or stopped behind a tree, which he did, the thing roared mad barks at him till he was back on true purpose once more. Well, this one horse-winning night, Conall was the halfway back home but he’d wandered out through some gate into a soft part of a field full of weeds, and thought to himself that it might just make a good enough bed for him, with the dog losing the mind across the road for growls and barks. There was a moment of stillness, then these wild white beams shot to life out of nowhere, only burning yellow the whole road. A second later and they shrunk down smaller and smaller and then a tiny wee car only tore along the tar macadam right at them, full speed, and the driver screaming to clear out the way, calling them all the foul names he could muster in his imagination till the car only jolted, swerved, rolled and finished upside down in three odd foot of ditchwater, wheels still spinning and the fella inside killed.

Thing about it was, Conall was wearing his green jumper with the orange stripe at the time.

The boy that went and got himself killed was Billy McKinley. He was a piano tuner from two towns over, and he was racing his way to urgently tune a piano, so the story went. Conall didn’t expect to witness Billy McKinley’s death at 4.17am off the North Road, but that he did. A whole party load of people were waiting in a room one town over the other direction with an out of tune piano, trying to keep safe some whiskey for Billy as a means of payment, but in the end it went drunk. People only found out the truth the next day. Billy’s car rolled four times. Billy inside bit out his tongue and spilled the leavings of his can and hit the dashboard at the same speed as the car was travelling, eighty eight miles per hour. What I’m getting at here is Billy’s blood-curdling revenge. Conall is willing to swear on any religious book you set before him that Billy McKinley, the speeding piano-tuner, haunts his green sweater with the orange stripe even today. Whenever he puts it on, he can feel Billy in the room, sitting in some chair with his empty spilled can, raging at him. More than once he claims to have heard a piano go playing out of tune at him. This is what happens when a man retires. He loses perspective. I put it down to this, what happened when Conall’s morning newspaper didn’t arrive one morning.

He was sitting at his table with the dog Red Bob at his heel, shovelling his porridge like an old plough.

“Sure isn’t yesterday evening’s paper as good?” his wife said. “What can have happened since last night? I’ll go fetch that for you.”

“Arragh, don’t stir. The boy will be along now. He came off his bike by Barrow’s field when that bored daughter they’ve got on their porch morning till night tried out catching him in the head with stones, or he stopped and talked another boy into splitting his round on account of the headwind bad enough to stop birds taking off, and how far up the hill we are. I’ll give him some talking to when he arrives, count on that much.”

Conall made it to his tea and toast, and then to another slice with marmalade, then a yoghurt, then some watermelon.

“Will you not stop eating breakfast just to have the paper with it? You’ll boil the guts out of yourself with indigestion,” his wife said. And that he did. Conall came from a long line of Donoghue men who ought really to have stuck to a diet of lettuce, carrots, beetroot and water on account of their acidic constitution, but instead saw nights spent bedridden, rolling in reflux agony lived out as some type of war declared between their body and themselves, and how they would no way be first to flinch. Pints, pastry, cigarettes and olive oil all went into the arsenal. Whiskey, sherbet, cream cheese, the kind of things to scald through a man’s guts and echo through the whole room doing it, all of that went down as an out and out act of war. His wife Molly, bolt awake beside him in the sheets listening to the thing seethe and froth and the swearing out of him, wild enough to churn butter.

“Look,” she said to him, “the racing isn’t on till three. Why not head down to Dannagher’s and ask what happened to the paper? Better yet, buy one.”

“Not the point, is it? I mean, we had a trusted agreement. It isn’t about me having to go down there and get it myself. It’s about them bringing it me. Anyroad, it’s already the afternoon. The morning press is out of date. Goes out of date soon as you finish your toast and anyone knows it.”

“Well, I’ll not have you moping and sulking around this house ‘till your horses arrive on screen at three. I’ve things to do. I’m meeting the girls. You need to go down there and kick up a little. I mean, what if the paper doesn’t arrive tomorrow?”

This hadn’t occurred to Conall.

“You’re right. If they think I’ll take this lying down, they’re only odds on to pull it again. And me paying the subscription at last year’s rate. I’ll wreck that little fecker, so I will.”

Conall walked the four odd mile road into town with the dog Red Bob at heel and his stick heard a good acre in every direction smacking off tarmac, shocking crows out of trees and disturbing field mice in the long rushes. Going the lazy way you veer leftward and cut across Foyle’s rested field to save following the long curve, designed for haulage trucks only and to no other man’s benefit, so Conall and the dog Red Bob kept their heads low on account of Dan Foyle being a vile, desperate daytime drunk and conjuring jealousies in his head, about his wife and men in the town. You’d often as not see squad-cars parked on his land, called out under the lie that his farm was under attack by robbers, just so the guards would arrive and look the place over and who knew, turn up a man in his underpants hiding out under hay bale or low between the ditches with electric pink lipstick all over his frozen white body.

“He bought that lipstick himself, specially in Gray’s pharmacy,” Conall told the dog Red Bob. “Bought up all nineteen sticks. So he’d know if he seen it on a local man, what it meant. Gray’s never got any more in for how god awful ugly it is.” Sure enough, there was a squad car at the porch.

Conall knew the land better than any man in the town. Forty two years he worked as grounds man at the Clonliffe Estate. He had dragged that place up out of raw wilderness with his own hands, sunburnt and rained on and frozen, sober and drunk. He knew well every thicket, every stray weed-patch, and had named all the deer, the grouse, the horses and the waterfowl, and they weren’t always polite names either. There was one deer he just called Bastard. It was a gold brown buck, and whenever he saw Conall he charged him, head on full-tilt, and there were chewing noises out of his mouth like he was trying to talk. First time out, Conall figured him for possessed. He got to know the buck though, and how he had named him well. His father, Conn, had been grounds man before him too, but had kept the flora nice and thick and wild and good for hiding in for local hoodlums, rebels, robbers and any folks hunted by the realm. He had taught young Conall what it is to trap an animal, how to foster a certain tree or flower in just this place, which ones like rivers and which hate them. Which ones hate people too, and intentionally cause them to sneeze. He claimed there was only a Puca hiding in there too, deep into the gorse.

“True wilderness attracts true wildlife,” he said. He claimed the Puca liked to drink local poitin with him and smoke oul cheap tobacco, and rate the women in the town out of ten. He had a roving eye. Tell ye the truth, the conversation out of the Puca was a little coarse for Conn, especially after enough to drink, which was saying something, so Conn had to learn the local area that little bit better to be sure of avoiding him on the harder moonshine nights. Conall never did find that Puca when the job fell to him, and he cleared all of the gorse away. Fact was, he doubted its existence.

Dannagher’s was a post office, a newsagent, a hardware store, a certain kind of bank, a certain kind of bookies, a pub and an undertaker. Paul Dannagher sat on a high chair behind his counter all day, smoking and reading the newspapers cover to cover from off the shelf. All he had to watch for were the schoolboys robbing out of his sweet jars, and the animals that from time to time made it in for shelter out of fierce weather. The only animal allowed in was the dog Red Bob, on account of how he seemed to possess that one true pure charisma. Everyone in the town said it, and he could get away with what he liked. He put this to the test, too. He chewed duvet covers off Mrs. Gallagher’s washing-line two weeks straight, he fouled up the Eire Óg pitch something wild after ruining the orchard out the back of Lacey’s field. Anyway, it was things like this. So, on that morning, the dog Red Bob arrived in the front door through the hung beads and Paul Dannagher set down his cigarette and newspaper.

“Well if it isn’t the high king,” he said. He fetched out a tin plate and a piece of the oul sandwich he was finished with anyhow, and laid it down by the dog Red Bob.

Want to read some more? Buy the book here on amazon

Posted by : Unknown

Thursday, 29 October 2015

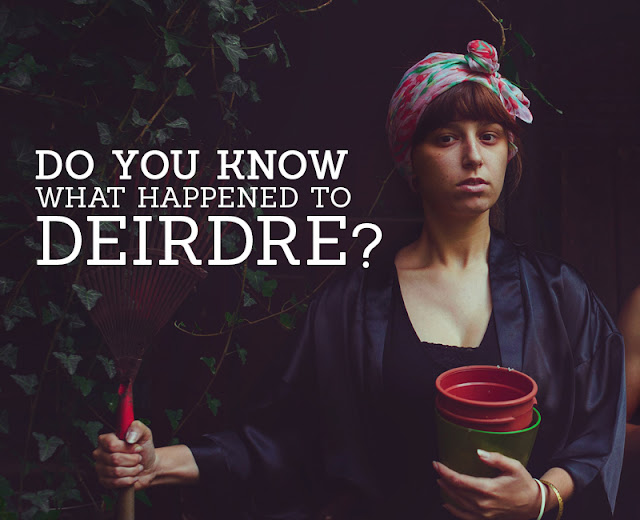

Do you know what happened to Deirdre?

Deirdre of the Sorrows

It's one of the most famous tales in Irish mythology, but so many Irish people don't know anything about it. It's like a cross between Rapunzel and True Romance, Bonny and Clyde and the little mermaid, only it's hundreds of years older and much more bloody.

It's the story of a howl from the belly of a pregnant woman. She was preparing food for her visiting high king, Conchobor, when the unborn baby within her let out a craven screech, unlike anything anyone had ever heard. It was enough to set his soothsayer on his feet.

"This child is cursed," he said, "she will be born too beautiful for this world. She will cause horrors and bloodshed, war and mayhem." He took his seat again at the table. "It's what no one wants to hear, but you need to kill her now, before it's too late." The mother was horrified, letting out a screech of her own and dropping her serving dish onto the tiles, but the king stood by her. He promised to take the child away when she was born, raise her as his own in seclusion from the outside world where she could do harm and, when she was of an age, marry her and make her his queen. It was what no one wanted in particular, but it was the high king's will, he had spoken and so it was decided.

It was many years later that Deirdre was out in the enclosed yard, in the grounds of the high king's castle with her handmaid and the conversation had come around to talking about men, once again. In all her years, Deirdre had never seen a man. None had been allowed next or near her by the king, to provide against the horrible prophecy coming true. But still, she had in her mind the kind of man she would have preferred to the king. She pointed out a raven, drinking blood from the snow in a nearby field.

"When I'm of age, I'll have a man with skin as white as that snow, hair as black as that raven's feathers and cheeks as red as that blood, and I'll accept no other."

"You're promised to the king," the handmaid protested, "he's raised you to become a great queen."

"We shall see," Deirdre said.

It wasn't much longer until she found a man with exactly that appearance. He was working for the king in a nearby field. A young man by the name of Naoise, one of the sons of Uislu. Right away, she ran over to him and jumped on his back, refusing to let go until he agreed to run way with her and protect her from whatever happened. At first, Naoise refused, knowing full well Deirdre was promised to the king, but the more he looked at her, the more he realised he was already falling in love, and was ready to do anything for her. Finally, Naoise agreed to run away and take Deirdre with him. He recruited his brothers and formed a formidable party of warriors, fleeing into hiding from wherever the high king could find them. The king was furious, and dispatched a crew of ferocious trackers and killers to find them, headed up by Fergus, his most prized warrior, who hunted them to the very edges of the land and even as far as Scotland.

Finally, an offer was sent to Deirdre, Naoise and his brothers. The High King would spare their lives if only they would return to his castle with Fergus. Well, they deliberated. It seemed risky, but truly, they had no place left to go really, lest they stray into lands they had no knowledge of. Deirdre agreed and they gang were escorted back to the High King's castle. What awaited them there, however, was not forgiveness and certainly not amnesty. Naoise and his brothers were killed immediately by Fergus and his men, and dumped in a large pit, which was covered over quickly with fresh soil. Deirdre was left a prisoner again, only now it was to get even worse.

The tale ends with Deirdre aboard a chariot with Conchobor, the high king, and his chief warrior, Fergus.

"Deirdre," Conchobor asked, "whom do you hate most in all the world? Is it me?"

"No, sire, it isn't. Not quite."

"Who then?"

"Why, it's Fergus. The man who murdered my beloved and his brothers."

"Very well then. As a punishment for trying to escape, you shall be shared between myself and Fergus for the rest of your days. "

This final horror was too much for Deirdre. She looked ahead and spied a low hanging rock approaching and then, when it arrived, she raised her neck so it would catch her head and take it clean off. This was her final revenge against her king.

So there you have it. Not the cheeriest of tales, but then this is Ireland. If you were interested enough, I'm launching Sour. my novel based on the myth at a bookshop in Dublin on November 5th. More details here if you're interested.

Or read an Amazon Kindle sample here:

Posted by : Unknown

Tuesday, 22 September 2015

How to tell if you're in a Patricia Highsmith novel.

|

How to tell if you're in a Patricia Highsmith novel.

You happen upon someone from an especially wealthy background, much less deserving than you of such luxury. This happens weekly.

Your knowledge of classical culture, from delighting in Leider by Schubert to correct appraisals of 50s American expressionism is shared by your whole social circle.

All the 50s American expressionist paintings are fakes, painted by someone you murdered.There are certain colours of sweater, hemlines, hats, cuff-links and turns of phrase that people deserve to be murdered for.

At some point you will visit a foreign city and sample its teas and customs with a certain air that these customs are where we have come from, and should never be fallen back upon, though you will have a phase of going native, if only for an afternoon, and if only with some impoverished local who you'll thoughtlessly hurl in the trash as soon as it all stales.

Conventions in afternoon alcoholism must be observed at all times. Gin and tonic as an aperitif follows the two beers for lunch and the afternoon Calvados with coffee.

You might be gay, but it would be boring to actually say so.

Italians, French, Spanish, British and American waiters all behave completely differently, but each one adheres strictly to their national pattern. The same is true of taxi drivers, receptionists, dogs and people drinking coffee, carefree on sun-drenched patios.

You have an enemy. You may not have had one since primary school and you're fully aware life is plenty tough enough already, but you have one nonetheless. At times it will feel like you have the upper hand, then the reverse will seem true. The whole chess match will invigorate you out of the non-homicidal stupor in which you've been languishing for months.

Identities are boring. Change yours at will by adopting phonetic accents of comic genius.

Wash often, but only as a metaphor.

A visit to your next door neighbour must be preceded by a sealed letter two weeks in advance, inquiring as to their general good health and knowledge of local gossip. This is to be followed up with an afternoon telephone call, between Calvados and gin, where you can verbally dance around your mutual loathing and the plots you're fostering against one another. An invitation will then swiftly arrive by card to dinner at theirs the following night.

Nothing beats socialising with people you hate, especially in the company of people who don't especially care either way. Lace every phrase with codified references to ways you can blackmail them. You struggle to decipher their codified references.

You have an enemy. You may not have had one since primary school and you're fully aware life is plenty tough enough already, but you have one nonetheless. At times it will feel like you have the upper hand, then the reverse will seem true. The whole chess match will invigorate you out of the non-homicidal stupor in which you've been languishing for months.

Identities are boring. Change yours at will by adopting phonetic accents of comic genius.

Wash often, but only as a metaphor.

A visit to your next door neighbour must be preceded by a sealed letter two weeks in advance, inquiring as to their general good health and knowledge of local gossip. This is to be followed up with an afternoon telephone call, between Calvados and gin, where you can verbally dance around your mutual loathing and the plots you're fostering against one another. An invitation will then swiftly arrive by card to dinner at theirs the following night.

Nothing beats socialising with people you hate, especially in the company of people who don't especially care either way. Lace every phrase with codified references to ways you can blackmail them. You struggle to decipher their codified references.

You never derive any pleasure from food. Tinned sardines on dry crackers would do it, and frequently does, served by your maid on the veranda overlooking the tennis court with champagne.

You believe pop music is for children and Jazz is where the line is drawn as far as tolerable musical decline from Monteverdi.

There is probably a wife or girlfriend somewhere you really ought to be getting back to if only you could be bothered.

If you liked this, you might like my novel, Sour, telling an old Irish myth as a modern murder story:

You believe pop music is for children and Jazz is where the line is drawn as far as tolerable musical decline from Monteverdi.

There is probably a wife or girlfriend somewhere you really ought to be getting back to if only you could be bothered.

If you liked this, you might like my novel, Sour, telling an old Irish myth as a modern murder story:

Posted by : Unknown

Saturday, 20 June 2015

There isn’t any science to any of it.

We found Black dead drunk slumped over his desk the Tuesday

morning. Bottle of compound beer emptied by his screen and several more rolled

off to other places. People crammed into the room to see and right away began

trying to bring him to. I said:

"Why not let him be? The guy's just won is first

sale."

But it wasn't a popular sentiment.

We had spoken and knew each other a little. Both of us had

joined up to the compound the same day and waited in reception together. He was

at his snout plenty, scratching it, rubbing it over. He wore a full pressed suit

and tie owing to how he had just come from work. He was sanitary for a badger

but there was a lot of something came masked by his cologne and I couldn’t be

sure but it seemed he sported a black eye. The receptionist brought me through

to the interview room first of everyone to meet the three recruiters behind the

desk.

"We have to prevent certain types making their way in

here." They told me. "We have to ensure we don't get any kinds who

just show up, take in a few meals, enjoy something of a holiday only to leave.

Then there are the types on the run from the law, from debt collectors, from

their wives." They asked me what my job had been.

"I worked in freight. A stevedore. The guys that load

and unload ships. I was one of those." As it happened I had worked in

advertising but it was no concern of theirs.

"We've decided to put you on probation. We need you to

prove you really want to be a part of what we're working for here. It's no

party. We're a no nonsense operation. We all chip in, quite often above and beyond.

For that is what it takes. It gets tough. There are early mornings. Late

nights. The crops require constant care and attention. Are you sure you still

want it?"

"I definitely want it."

"Another thing is we have to confiscate all you've

brought with you. In the commune we share everything equally."

"You mean my car?"

"Yes, the car."

"That's all right."

"And everything else too. You no longer own

anything."

Afterwards Black told me he made the mistake of coming

forth with how he had been a salesman. On account of how lying was behind him.

The compound was to be his fresh start. He opened his wallet and showed me a

photograph of his house, of his old car and his boat. He told me he hadn't sold

them, he had given them away. That was all a part of it. These things were but symptoms

of his illness. This place was the cure.

I met him again about a week and a half later. I was out in

the field spraying the sprouts for flies. He passed me coming back in, still

wearing that full suit. The rest of us were all in the casual sweatshirt and

jeans type get-up they handed out at registration. He said to me:

"I can't understand they haven't given me anything else

to wear. It's all I have with me. They keep washing and handing it back. I

thought they'd supply us with a toga or robes or something. I feel like a real

weirdo in this."

He showed me a photo of his son, Martin. He kept talking

about this kid. He seemed the difficult type. He was a cellist. In the photo it

seemed like the boy was looking right through me. But he could do no wrong by

Black. He was only the one half badger. He lived back out there with Black’s

ex-wife. They had helped him through much of the drinking and the clinic but

had been dead against his hanging it all up to join a commune.

The three behind the desk had informed Black he had a month

to pull in two large in sales or he was out. That was his probation. He had to

sell the vegetables. Then after that it was three large. All this farmed

produce needed to go toward paying for irrigation, electricity, the kitchens.

They needed someone to sell it.

He sat by his desk early morning into the evening.

"Afternoon miss, I only called to inquire if I might

be able to interest you in the finest, the best value for money organic produce

from right here in the..." Then he went back and redialled.

"Good afternoon mam. I wonder am I talking to the manager of the shop. That's, yes, that's fine too. Well, I was calling to see if I might be able to interest you in the very finest, the very freshest..."

"Good afternoon mam. I wonder am I talking to the manager of the shop. That's, yes, that's fine too. Well, I was calling to see if I might be able to interest you in the very finest, the very freshest..."

"You look like you're on tough detail." I said. I

poured him a coffee.

"It's not easy either. Try selling vegetables from a

hippy commune. Everyone believes all we do around here is sit in circles smoking

pot beneath the oak trees."

"That or worse."

"Worse, exactly. Go try selling groceries from a drug

addled sex farm. But I can do it. Two large in a month, I have to. I have to do

it. I can't go back out there. It's cut throat."

He utilised age old techniques peppered with new methods

like what he told me was neuro-linguistic programming. He only mentioned

positive things. He made sure their answer to his every question was yes. It

coaxed favourable chemicals out of the brain. It set lucrative patterns of

speech. Then, each night, the managers brought him in for a full report. He

produced his flow charts and projections. It usually ran till late. We would

some of us stay up and listen outside. I couldn’t take much. It felt bad

hearing a badger go through that kind of thing. They are proud animals and that

sounded awfully demeaning.

I tried talking with him some at suppertimes. He talked

about being a failed painter. He was a failed poet too. Everyone in sales is deep

down something else. But when he visited the west, or the countryside, and he

stood alone beneath a ferocious yawning sky in every direction, with an equally

ferocious sea out before him, that was the only time he was content. He gave

that a lot of thought. So one evening he had packed up his car and told his wife

it was all done with. That was where the black eye came from.

Then the Monday night he strode in suit jacket over one shoulder,

tie loose and already somewhat drunk. He

had his figures all printed. He was sure and reminded them that he was the

king. Yessir. Sale

A few of the stoats helped him to his room and he was

allowed sleep it off. There was a whole lot of hot air but in the end nothing further

was done about it. He hadn't drunk any more than his commission got him anyhow.

I was put on cleaning duty. He had gotten through two cartons of cigarettes,

the nine beers and a hip-flask and there was ash everywhere. He had really

enjoyed himself in there. I for one was glad he had made the sale. I would have

missed him. And when it came down to it we were all of us in the same boat.

I cleared up the charts and sales sheets and finally a

chocolate bar wrapper and a receipt. It was a credit card receipt. It was in

the name of Martin Black and it had just paid out two large. I pushed it to the

bottom of the bag.

They moved him by the window in the main dorm. He got

himself a bedside locker at that. And a couple of days at ease, they didn’t

even call upon him to work crops. He hunched over the fence afternoons in

shirtsleeves rolled up and watched us. I tried to make out how his face seemed

but a badger is inscrutable. Thursday came by the first of the month. I visited

the office on cleaning detail and he was back in there. His suit jacket caught

the light handsomely. He had the coffee machine emptied already by ten am .

Posted by : Unknown

Sunday, 7 June 2015

Samuel Beckett's style.

You

leave both your albums at home, I said, the small one as well as the large one.

Not a word of reproach, a simple prophetic present, on the model of those

employed by Youdi. Your son goes with

you, I went out.

This, excerpt from ‘Molloy’, might be one

of the few instances in Beckett wherein we get something like a glimpse behind

the curtain. Notoriously vague as to the explanation of anything he ever wrote,

“If I knew what it was about”, he said, “I would have said it”, Beckett is an

artist of pure form, almost perhaps to the extent of which the ensuing content

might take its import purely by relation to it. In that it ensues. In that

something must ensue from form. Throughout the development from the

post-Joycean pyrotechnics of ‘More Pricks than kicks’ through to the clipped

monotone utterances of the very latter stage, much more striking than the

fixation upon the paring down of prose there can be traced the development of a

simple, almost binary relation running through close to every sentence. Nowhere

is this more visible than in his mid to the beginnings of his latter work, a

period encompassing in particular The Trilogy and The Four Novellas.

No less than the sense that these works

are made up from endless heaps of meandering digressions, each superceding the

last, to no discernible end other than to have something told, we are

indoctrinated quickly into pleasant familiarity with the peculiar timbre, a

constant cadence establishes itself through these pieces and we acclimatise

ourselves to a pattern, a sequence of patterns, presented as fiction.

Perhaps

I am wrong, perhaps I shall survive Saint John the Baptist’s Day and even the

Fourteenth of July, festival of freedom. Indeed I would not put it past me to

pant on to the Transfiguration, not to speak of the Assumption.

A typical Beckett phrase the like of this

makes a scaffold of its dead language, the cliché, in this case two; I would not put it past me and not to speak of. To this foundation can

be added anything, any flight of fancy or self indulgence or, as in this case,

technical nous, (the echoes between John the Baptists fate and resonant images

from Bastille day or quirks like festival of freedom and pant on), in full confidence that it can be easily

stomached thanks to this grounding in the banal. This banality Beckett becomes dependent on to

clear a path for him, both through the gluttonous stylistics that marred his

early work , forcing it into a palatable, dare we say it, bite sized, shape,

and also imbuing the narrator with some sense of normalcy, even if it’s only

the pretence that he’s too exhausted to bother with thinking up a more

interesting way of saying it.

The Trilogy represents the summit of

Beckett’s prose because it’s the point where he has honed this sense of dead language

past the near catatonic lists of ‘Murphy’ and ‘Watt’ and established it as

perfect counterpoint to the sudden linguistic tangents his sentences constantly

shock us with. He has abandoned both the urge to dazzle the reader and to numb

him into submission and introduces a new sense of tongue-in-cheek, nurtured

through Mercier and Camier and the Four Novellas, in which any horror or any

significant incident is punctuated with a certain kind of knowing grin.

One

of these days he will astonish us all. It was thanks to Sapo’s skull that he

was enabled to hazard this opinion and, in defiance of the facts and against

his better judgement, to revert to it from time to time.

There are no less than six cliches in

the above phrase and in The Trilogy, a steady reliance upon cliché develops,

particularly in the first two books. Cliches are the bread and butter of the

sandwich, sentences frequently kicking off with some or other platitude or using

one to conjoin two or more eddying streams of prose. A large part of the

quality of Beckett’s writing comes from not being able to guess where it will

have gone by the end of the sentence, let alone the following one, or the

narrative, and this goes as much as anything for the rhythms. Cliché invests the same sense of cold, almost

mathematical, language for which he had previously struggled with lists and

drawn out variables, while initiating a particular form based in the appearance

of spontaneity or off-handedness. It’s as if each sentence, or phrase, is

started off, or built around, a stock dead frame and then, once the floor has been

given it, is allowed wander at random off in any direction until it eventually dies,

at which point we begin anew. Practically

the only way this can be arranged into a narrative of any progression would be

in the first person, struggling to tie narrative ends together through acrobatics

of lateral thinking. These acrobatics, or rather the relation between these and

the dead language, become the point of the prose.

The use of cliché emphasizes the notion

of given ‘stock’ language, handed to, or even enforced upon, the user. A lack

of all thought, personality or any welling up of feeling into verbal

expression. A phrase with a seemingly universal significance which actually

serves to express nothing. Moreover, its use here is so self conscious

that it almost actually achieves what

Beckett had so long striven for and so often referred to. In hanging the

structure of his prose from it, cliché, by its emptiness, by its communication

of linguistic vacuum even extending to thought, robs every phrase of any hope

of actual, verifiable communication. Something which by its very nature

expresses that there is nothing to express and no way to express it.

Scrupulous

to the last, finical to a fault, that’s Malone, all over.

That’s

the bright boy of the class speaking now, he’s the one always called to the

rescue when things go badly, he talks all the time of merit and situations, he

has saved more than one, of suffering too, he knows how to stimulate the

flagging spirit, stop the rot, with the simple use of this mighty word alone,

even if he has to add, a moment later.

The more you read a sentence like this,

trawling for cliché, the more blurred the lines become between what it is

you’re after and what might possibly

qualify. Parts of sentences such as ‘he’s the one’ or ‘knows how to’ or ‘a

moment later’ carry that sense of having come packaged almost as much as ‘stop

the rot’ and this extends deeply into every phrase. No longer is it a case of

cliches peppering otherwise creative prose and a safe juxtaposition, but the very same prose, even what could be called

‘high’ Beckettian prose, verging almost on poetry, begins to read suspiciously.

He

would stand rapt, gazing at the long pernings, the quivering poise, the wings

lifted for the plummet drop, the wild reascent, fascinated by such extremes of

need, of pride, of patience and solitude.

There’s little doubt that a significant

part of Beckett’s reputation as a writer comes from passages the like of this, pointing to a keenly poetic bent, never

fully satisfied with his attempts at poetry. But no longer does it appear devoid of cliché.

Aside from ‘he would stand’ and anything else someone might be able to spot,

the sense of a kind of banality in cadence rings very much true. Gazing at

the…, the…, the…, the… Extremes of …, of…, of… and…

The sense of all language being cliché.

What writing in the French drew out of

Beckett was the sense that he had lost all

language , had mummified his natural English with the straightforwardness

of a Romance Language while at the same time setting down a kind of French that

seems it’s been translated from an English text.

Anthony Burgess was fond enough of the

following phrase from ‘Murphy’ to return

to it time and again as an example of how ‘satisfactory’ Beckett’s English was.

The

leaves began to lift and scatter, the higher branches to complain, the sky

broke and curdled over flecks of skim blue, the pine of smoke toppled into the

east and vanished, the pond was suddenly a little panic of grey and white, of

water and gulls and sails.

Posted by : Unknown